Why Is Saving Money Hard

We've all been there. That moment you wake up and can't believe how much money you spent last night with your friends. Or when you check your bank account statement and can't fathom how the numbers got so low.

We're all told time and time again that it's important to save up for the future, yet our behavior just doesn't seem to match our future selves. What gives?

First off, know you're not alone. A majority of the US population saves between 0%-5% of their income every month, which is a pretty big departure from the suggested 15%. (CNN Money)

Most of us get our paychecks and immediately spend them, whether it's on apartment rent, student loan payments, utilities, getting an insurance policy, groceries, or boozy nights out. Sound familiar?

Since this behavior is so widespread, and, quite frankly, irresponsible, there's gotta be an explanation.

The science behind our spending habits

Perhaps it's that we're generally bad at understanding our finances. But according to science, the problem lies elsewhere.

Studies show that poor financial choices are associated with high levels of in-the-moment-living. (American Psychological Association) And the strongest predictor of smart financial decisions is not our level of financial literacy – it's how often we stop to think about the future.

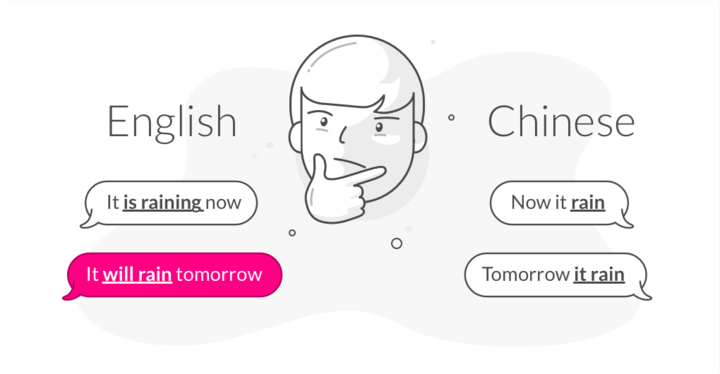

Not convinced? Consider this: people who speak certain languages are better at saving money than others. Yeah, you read right.

Those who speak languages that use the same verb conjugation for present and future tenses are among the world's biggest money savers, such as the Chinese and Germans. Since they speak about the present and the future the same way, they've trained their brains to think about them similarly, which makes it easier for them to save money for the future in the present time, according to behavioral economist Keith Chen .

On the other hand, people who speak languages that use separate verbs for the present and future are much worse at saving money, such as the Americans and Brits. Since the future feels more separate from the present, it's harder to think about them similarly.

It's no coincidence that Americans and British are some of the worst savers on the planet.

So there we have it. It's hard for us to save up because we tend to value the 'now' over the 'later.' In behavioral economics speak, this is called 'present bias.'

Why it's so hard to think about the future

But when you think about it, it's weird that it's difficult for us to behave in ways that will benefit ourselves in the future. After all, our future selves are just as much 'us' as our current selves.

Why is it so hard for our brains to understand that?

According to science, our mind thinks about our future selves in the same way it thinks about complete strangers.

Here's what happens: When we think about ourselves, a region of the brain called the medial prefrontal cortex – or MPFC – lights up. When we think about other people, activity in this region powers down. And when we think about someone we have absolutely nothing in common with, it activates even less.

Here's the kicker: the further out in time we try to imagine our own lives, the less activation we show in our MPFC, according to fMRI studies. (ResearchGate)

In other words, our brains act as if our future self is someone we don't know very well, and, quite frankly, someone we don't care about very much.

This makes intuitive sense, notes Emily Pronin , a psychologist at Princeton University. One of the defining differences between the way we think about ourselves and the way we think about someone else is how we're able to experience our own thoughts and emotions versus someone else's. She explains:

"We experience our own [thoughts and emotions] internally, whereas, for other people, we only know what their thoughts or emotions might be. So the future self – and in that same way, the past self – are more like another person than they are like the self because we can't experience the feelings of a past and future self like we can with the present self."

So what can we do about this?

To get better at saving for the future, we'll have to trick our minds into sympathizing with our future selves. If we teach ourselves to experience the thoughts and emotions of ourselves in the future, can we make better financial decisions?

That's right, according to science.

In a clever psychological study, a group of college students was shown images of their own faces that were digitally altered to appear 50 years older. A second group of students was shown images of themselves that were unchanged.

Those who'd seen a glimpse of their future selves said they would allocate about 30% more money on average to their 401(K) than the students who were shown pictures of their current selves.

"So the lesson from that is anything that we can do that will increase how concrete and salient our future self is – that's the type of thing that can help us make better decisions," said Magnus Herschfield , the pioneer of this study.

How can we do that ourselves? For one, we can use the AgingBooth app, which lets you instantly 'age' ourselves by adding some wrinkles and grey hair to a recent image. Perhaps, like the research subjects above, doing so will make us more motivated to save money for our future selves, because we'll be able to better empathize with ourselves.

Alternatively, Stanford University Professor Jane McGonigal suggests making a list of things you're interested in – such as food, travel, cars, insurance, AI etc. At least once a week, do a google search for "the future of __" (one of the things on your list). Read an article, listen to a podcast, watch a video – and get some ideas of what the future of something you love might look like.

A final way to get better at prioritizing our future self is to make it our default option. "The lesson from behavioral economics is that people only save if it's automatic," said behavioral economist and Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler . "If you want to help people accomplish some goal, make it easy."

Lemonade's own Chief Behavioral Officer, Dan Ariely, agrees:

"We should just take [15, 20, or 25% of our salary] out of our paycheck directly, automatically, without paying attention. Put it into a different account, don't think about it."

His suggestion is backed by science. In a study, one group of people deposited their money in 'commitment accounts,' while the other group spent their money freely.

The first group ended up with considerably more savings than the second. Nudging yourself to automatically put money towards your savings and restricting your access to your account is a sure way to put your future self first.

You must be thinking: there better be an app for that. Well, you're in luck. Quapital lets you set various 'rules' to automate your savings. It allows you automatically transfer funds into your account when you spend less than you budgeted, or contribute a lump sum to your fund on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis.

The idea is that you can move your money automatically, so you'll save up for goals without having to constantly remind yourself.

Trick your mind into saving money

The moral of the story is that, quite frankly, saving up for the future is just not a natural human instinct. It's hard for us to save because it's difficult for our brains to think about the future in a concrete way.

But there's no need to lose hope – we can either trick our minds into imagining the future more effectively, or, perhaps more realistically, we can make saving money a default option for ourselves. That way, saving for the future won't be a choice, it will be automatic.

Put your future self first and save money renters insurance. Get a Lemonade policy in 90 seconds.

Why Is Saving Money Hard

Source: https://www.lemonade.com/blog/science-behind-savings/

Posted by: pagansatedilly.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Why Is Saving Money Hard"

Post a Comment